So many images represent Walt Disney. There’s that mouse, of course, and all the movies. So much music, all those cartoons, countless toys, but let’s not forget the comic books.

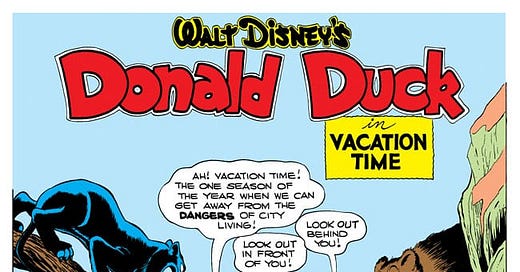

Disney characters appeared in different media. Take those Donald Duck cartoons, for example—animation of an exasperated duck with a funny voice. But there’s also an adventure series with Donald, his nephews, and a miserly Uncle Scrooge that was featured in comic books created by cartoonist Carl Barks.

Barks, who worked for Disney from 1942 to 1966, is now celebrated for his comic-book creations. Other people have depicted Disney’s duck but they don’t have their stories being reprinted in full-color hardbound books from Fantagraphics (the complete Barks series is slated to be completed by 2026).

What sets Barks apart are his stories, said Peter Schilling, Jr., whose book, Carl Barks’ Duck, was published in 2014. “It’s the writing as well as the art,” he said.

Schilling discovered Barks as a kid when he and his brother were avid comic-book readers. What Schilling discovered was that the comics that Barks created—anonymously under the Walt Disney umbrella—were different from those drawn by other artists. “We read other Donald Duck comics but they weren’t the same. They weren’t from that guy,” he said.

That guy—Barks—toiled in anonymity until late in his career but the secret’s out now. “I look at his comics like little movies with Donald Duck as Cary Grant, whose career ran from comedy to serious drama,” said Schilling.

Along with his wide-ranging stories and explosive artwork, Barks was a creator of characters. He came up with Uncle Scrooge, Gyro Gearloose, the Woodchuck Manual, and the Beagle Boys, said Schilling.

As for a favorite story, Schilling cited several in his book but singled out “Vacation Time” as “a forgotten masterpiece.”

BASEBALL IN BLACK AND WHITE

A baseball novel of what might have been

Another Schilling book, The End of Baseball—A Novel (2008), depicts what have been had Bill Veeck, the maverick promoter, been able to follow through with his stated plan in 1944: buy the struggling Philadelphia Athletics franchise and bring in players from the Negro Leagues.

Veeck was a baseball man, through and through. His father, William Sr., was a Chicago sportswriter who became president of the Chicago Cubs. After his father died in 1933, Veeck became treasurer of the Cubs. In 1941, he bought the Milwaukee Brewers, then a Cub minor league property. Veeck raised attendance with promotions such as giving away live animals or scheduling morning games with free breakfast for overnight workers. Later, Veeck sent little Eddie Gaedel up to the plate, all 3-foot-7 of him, to draw a walk. Veeck’s also given credit for growing the ivy on the walls of Wrigley Field and setting scoreboards up to send up fireworks.

Schilling said Veeck had come back from WWII service where he was injured while serving in the Marines, with a plan to integrate baseball in sensational style. But after conferring with then-commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the deal was thwarted when another buyer took over the Philadelphia franchise.

Did Veeck actually plan such a move, three years before Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier? Schilling thinks so and his book imagines the season that might have followed, raising awareness along the way of some of the great players in the Negro leagues in the process and some of the problems they could have faced.

In real life, Veeck headed a syndicate that in 1946 bought the Cleveland Indians (now Guardians). He hired Larry Doby, the first African American to play in the American League. Veeck also signed Satchel Paige, another veteran of the Negro leagues and a member of the Indians’ World Series-winning club in 1948.

Schilling said he’s been questioned about his book’s title. “What do you mean it would have been the end of baseball?” some ask. Schilling said it’s a reference to criticism that likely would have raised at the time—in 1944—by those who didn’t want to see baseball integrated.

Share this post