World War II may have ended nearly 80 years ago but it lives on as a subject endlessly reviewed as fresh insight and information continues in an unrelenting deluge.

Movies and books haven’t stopped rehashing the great war since its conclusion, witness last year’s Oppenheimer and, now playing in your local metroplex, The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare.

Meanwhile, WWII offers an ongoing avalanche of literary material, exemplified by recent titles like Churchill’s Shadow Raiders: The Race to Develop Radar, WWII’s Invisible Secret Weapon; Madame Fourcade’s Secret War: The Daring Young Woman Who Led France’s Largest Spy Network Against Hitler, and Need to Know: World War II and the Rise of American Intelligence.

So vast and involving was WWII, it may be another 80 years before we stop writing books about it. There are always new aspects to explore or revelations about old aspects. The examination of men and women from all over the globe who put their bodies on the line, sometimes in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds, dictates that we take notice.

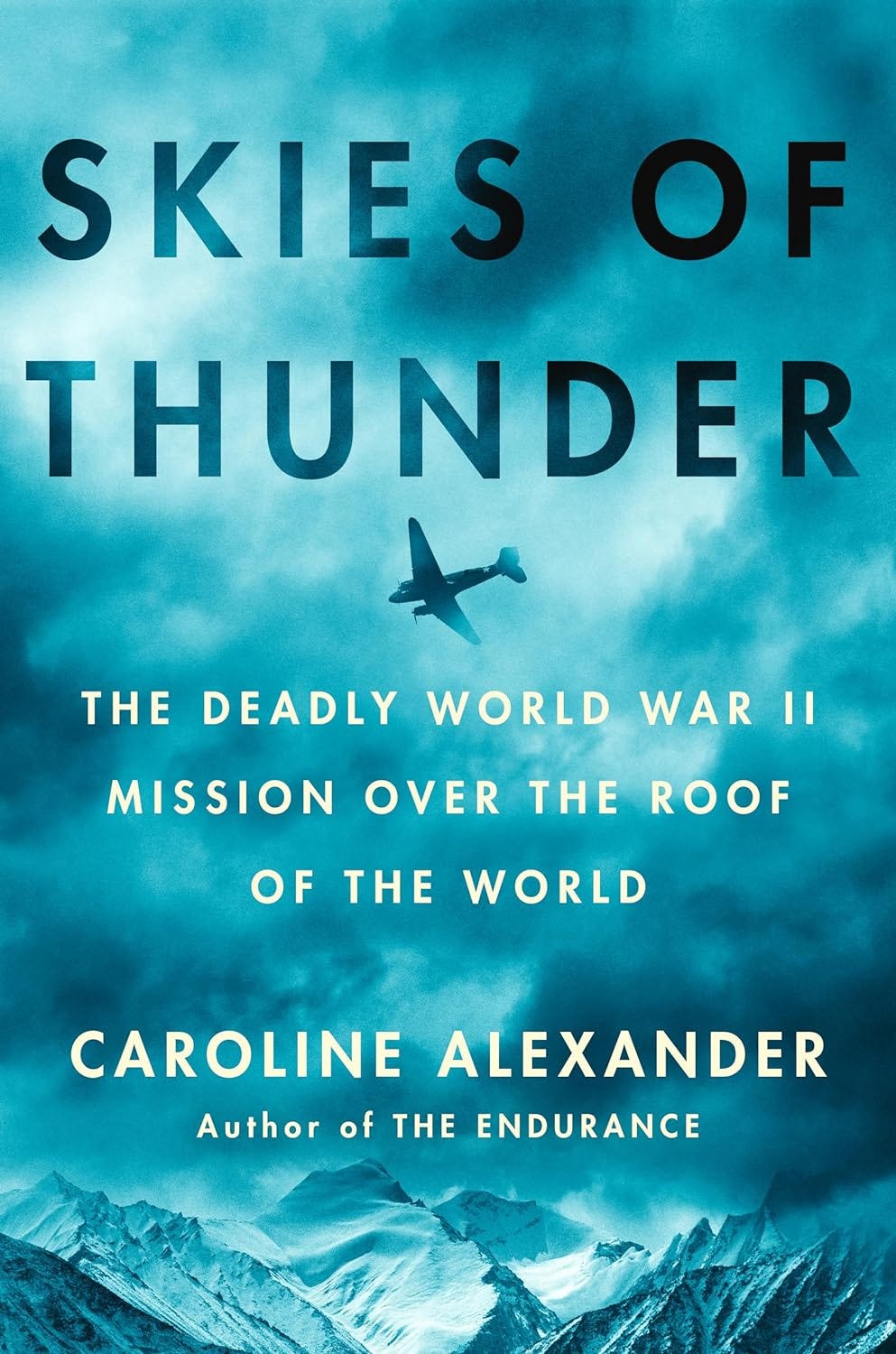

Caroline Alexander’s Skies of Thunder (Viking Press) examines the WWII heroes who flew transport planes in the China-Burma-India theater. During these times of rising tensions between China and the U.S., it’s worth noting that the two countries were allies in WWII.

Japan had attacked China years before Pearl Harbor and, by 1942, had all but sealed China off from the world. Alexander notes that the official line at the time was that America wanted to keep China in the war. The U.S. military didn’t want Japanese troops engaged in China to be diverted elsewhere in the Pacific.

But Alexander said that Franklin D. Roosevelt was also thinking about global politics after the war. Assisting the most populous country in the world—that wouldn’t declare an allegiance to Communism until 1949--could only bolster U.S. prospects.

Once Japan closed off Chinese seaports and gained control of the Burma Road, the only way to get supplies into China was by air. There was only one little problem: the air route required flying over the foothills of the Himalayas. As if navigating through the tallest mountain range in the world wasn’t daunting enough, pilots had to deal with frequent, intense storms over those mountains, the result of warm air from the Bay of Bengal colliding with cold winds from Siberia, said Alexander.

Storms proved to pose an even greater danger than enemy planes at a time when the existence of a weather phenomenon known as the jet stream wasn’t even known, said Alexander. “Pilots sometimes reported being shot up thousands of feet in a minute as they endeavored to fly by instruments,” she said.

Flights were scheduled around the clock regardless of the weather. The stormy weather proved to be a major obstacle, claiming 600 planes and 1,700 lives. Little wonder that flying the Hump also became known as traversing the Aluminum Trail.

Alexander said she first became aware of the airlift while undertaking an assignment for National Geographic on the large tiger refuge in Myanmar (Burma’s present name). After noticing that strange, jagged pieces of metal fencing in villagers’ gardens were made from pieces of fuselage from old WWII planes, she learned that the lush jungle was hiding a graveyard of crashed cargo planes.

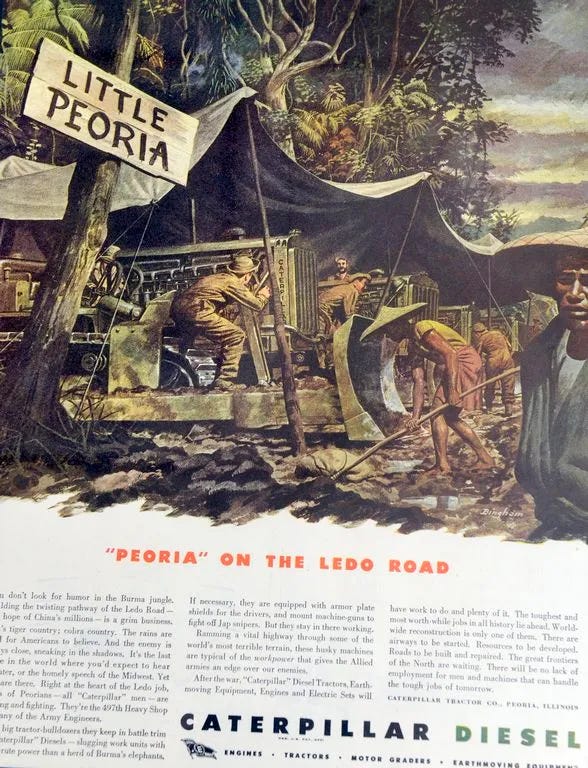

Alexander’s book also recalls how Americans sought to support China on the ground, carving out the Ledo Road, a route between India and China that required “a Herculean engineering project in challenging terrain and climate,” noted Matthew Delmont in Half American, a book about the contributions African Americans made during WWII.

The Ledo Road stood as a remarkable achievement, involving 15,000 American troops, almost two-thirds of them African American, along with 35,000 local Indian, Burmese, and Chinese civilian workers. It took a lot of heavy equipment to carve out a road in jungle terrain, sometimes working on days when as much as 10 inches of rain would fall, turning roadways into rivers of mud.

A lot of bulldozers were used, inspiring the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to call on the 497th Engineer Heavy Shop Company, made up largely of workers from the Caterpillar Tractor Co. in Peoria, to set up shop in the jungle.

While the road, completed several months before the end of the war, proved that Americans could pull off amazing feats of engineering under extreme duress, air power proved to be the difference maker in the war, said Alexander, adding that the heavy equipment used to clear jungle was all flown in.

By the end of the war, the Hump operation had revolutionized aviation infrastructure and transformed the way wars were fought, she said.

For more information on the China-Burma-India theater of WWII, I would also recommend Carl Weidenburner’s remarkable website: https://www.cbi-theater.com/menu/cbi_home.html

SKIES OF THUNDER