It’s a story of World War II but it’s also a story of politics, power, seduction, and intrigue. Did I leave anything out?

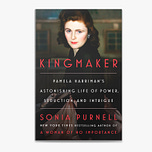

Pamela Churchill Harriman didn’t as Sonia Purnell’s book, Kingmaker, makes clear. The British biographer and journalist spent five years gathering information on Harriman’s life, including gaining access to a wealth of fresh research, interviews, and newly discovered sources.

Harriman, who died in 1997, is well-known as Winston Churchill’s daughter-in-law, the 20-year-old who played cards with Winston in the middle of the night when bombs were falling on London. But she was also a power broker whose influence extends to the present, noted Purnell, adding that it was Harriman who bolstered Joe Biden’s career back in 1988 early in the Delaware senator’s career.

Pamela Harriman got around, to put it mildly. She successfully wooed W. Averill Harriman, the wealthy businessman who came to London as Franklin Roosevelt’s “Lend Lease” representative in 1940—before America was in the war. Lend Lease was the result of Churchill’s efforts in urging FDR to provide a beleaguered Britain with much-needed war supplies—much to the annoyance of the U.S. separatist movement.

This was a time when England was just hanging on, rapidly running out of manpower, munitions, and supplies as Nazi forces loomed across the channel. But she did even more to advance “Operation Seduction USA,” as Purnell put it: she bedded generals, high-ranking officials, and representatives of the media (most notably Ed Murrow whose “This is London” broadcasts helped Americans experience England’s plight during the Blitz)—all for the sake of jolly old England.

She married Randolph Churchill and had his child, Winston II, but the prime minister’s son, awash in gambling problems, was a disaster as a husband, said Purnell. The pair were divorced following the war and Pamela found herself out of a job along with father-in-law Winston, as Clement Attlee and the Labour Party swept to power in 1945.

After moving to France, she tarried with playboy Prince Aly Khan before falling in love with Gianni Agnelli, the head of auto giant Fiat. After four years the couple broke up but Agnelli, whose own career is one for the books, never failed to call Pamela every morning at seven for the rest of her life, said Purnell.

In 1960 Pamela moved to America and married Leland Hayward, the Broadway producer with shows like South Pacific, The Sound of Music, Mister Roberts and Gypsy to his credit. Harriman enjoyed their 11-year marriage until his death. At age 51, she married Harriman, her lover from the war, and now 79 and a widower.

Being married to the elder statesman of the Democratic Party kicked off a new chapter in Pamela’s illustrious life—that of a person of influence. “Adversity galvanized her,” noted Purnell, pointing to how she countered the Reagan landslide of 1980 by pumping up Democratic hopes. Harriman reminded the browbeaten Demos that Churchill came back (getting re-elected prime minister in 1951) and that the Democrats could, too.

At her funeral, Clinton acknowledged that without Harriman’s support, he might never have been president. Purnell noted that it was through Harriman’s connections in Washington, her hobnobbing with the high and mighty, that allowed a young politician from the state of Arkansas to gain visibility and ascend to the national stage. A grateful Clinton named her U.S. ambassador to France, a position she held until her death.

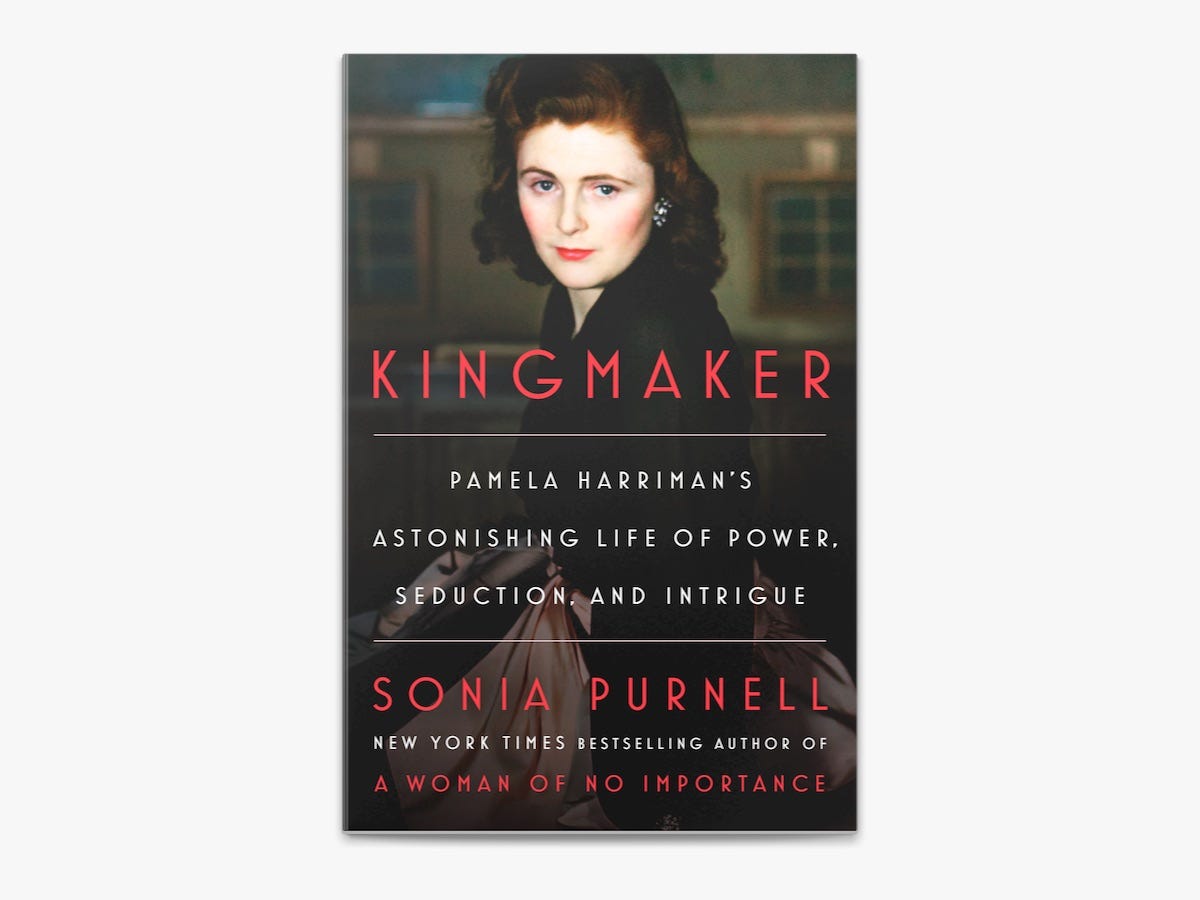

Pamela Harriman collage from the Literary Hub.

There was virtually nobody of substance in the 20th century that Harriman didn’t know or work with, Purnell said, ticking off a list that included such luminaries as Frank Sinatra, Ernest Hemingway, Truman Capote, Gloria Steinem, Bella Abzug, and Nelson Mandela.

Earlier biographies have painted Harriman as a sex-obsessed gold digger, a courtesan who craved power, as “the other woman” in her many relationships with married men. There were also issues with the riches she inherited by marriage. After a bruising legal battle in 1995, Pamela paid $11 million to Harriman’s stepchildren who accused her of squandering their trust fund.

“The seductress of the century,” as she was identified in one lurid account, was a colorful character. Following her death in 1997, Time magazine said Harriman’s life was “too implausible for a romance novel or Hollywood blockbuster.” But that was before eight-part biographies became a streaming standby. When asked about the possibility of a film version of Kingmaker, Purnell acknowledged, “There have been talks.”

Share this post